Marvin Minsky

Marvin Minsky

The Architect of Artificial Intelligence

The Man Who Named the Dream

If artificial intelligence has a founding philosopher, it is Marvin Minsky. Where others built machines, Minsky built ideas. Ideas about minds, machines, intelligence, and what it means to think. He did not merely help create AI; he defined its intellectual boundaries, ambitions, and controversies.

Minsky was bold, provocative, sometimes wrong in the short term, yet astonishingly influential in the long term. Modern AI debates about reasoning, modular intelligence, consciousness, and the limits of neural networks still echo arguments he made decades ago.

Early Life and Intellectual Formation

Early Life and Intellectual Formation

Marvin Lee Minsky was born in 1927 in New York City. From an early age, he displayed a rare blend of mathematical rigor, mechanical curiosity, and philosophical ambition.

He studied mathematics at Harvard, served in the U.S. Navy, and later earned his PhD in mathematics from Princeton. Computer architecture legend John von Neumann served as his dissertation advisor. At Princeton, among other inventions, Minsky built the Stochastic Neural Analog Reinforcement Calculator (SNARC), one of the earliest neural network machines, in 1951. This was decades before neural networks became fashionable again. From the start, Minsky saw intelligence not as a mystical phenomenon, but as something that could be understood, decomposed, and engineered.

In 1958, Minsky joined the staff at the MIT Lincoln Laboratory. A year later, he and John McCarthy initiated what was, as of 2003, named the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. He was the Toshiba Professor of Media Arts and Sciences as well as Professor Emeritus of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT.

Minsky taught and conducted research as part of the MIT faculty from 1958 until his death in 2016.

Genetics seemed to be pretty interesting, because nobody knew yet how it worked. But I wasn't sure that it was profound. The problems of physics seemed profound and solvable. It might have been nice to do physics. But the problem of intelligence seemed hopelessly profound. I can't remember considering anything else worth doing.

The Dartmouth Conference

The Dartmouth Conference

Minsky was a central figure at the 1956 Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, alongside John McCarthy, Claude Shannon, and others.

This conference coined the term artificial intelligence, established AI as a legitimate scientific field, and proposed that human intelligence could be formally described and mechanized. Minsky brought intellectual audacity to Dartmouth. He believed that building human-level intelligence was not just possible, but achievable within a generation. That optimism would shape AI research for decades.

Minsky also contributed his organizal skills to the conference. The broad, intellectual agenda was largely written by Minsky.

MIT and the AI Laboratory

MIT and the AI Laboratory

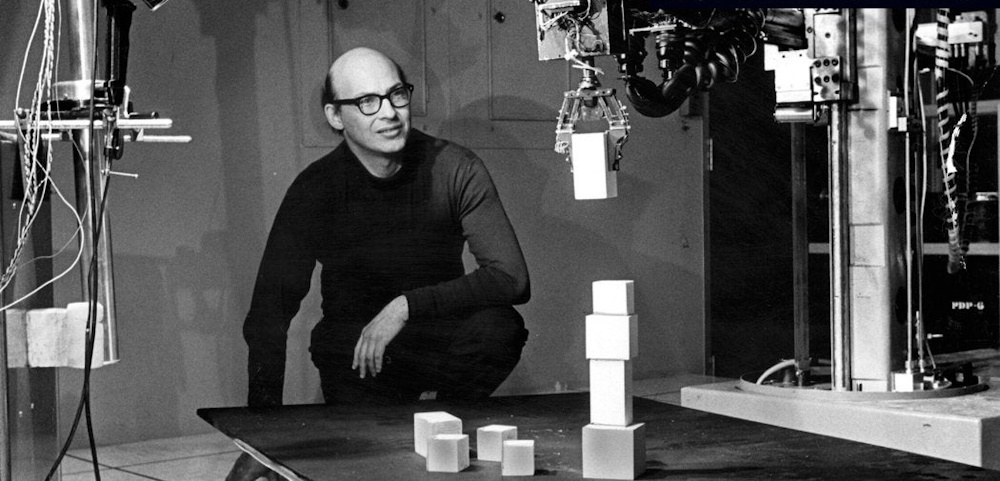

In 1959, Minsky joined MIT, where he later co-founded the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, which became the world's most influential AI research center.

Under Minsky's leadership, the MIT AI Lab pioneered symbolic AI, explored vision, robotics, language, and reasoning, trained generations of AI researchers, and influenced DARPA-funded research nationwide.

The lab was philosophical as well as technical. Like a philosopher, Minsky encouraged radical thinking, skepticism of fashionable ideas, and fearless speculation.

Symbolic AI and the Society of Mind

Symbolic AI and the Society of Mind

Minsky rejected the idea that intelligence was a single unified process. Instead, he proposed one of the most influential theories in cognitive science: The Society of Mind.

Published in 1986, Minsky claimed in The Society of Mind that intelligence emerges from many simple, non-intelligent agents. He argued that minds are collections of interacting processes, and consciousness is not a single thing, but a pattern.

This framework anticipated modular AI architectures, influenced cognitive science and neuroscience, and foreshadowed multi-agent systems and modern AI pipelines. Even today's large language models resemble Minsky's vision more than he might have expected.

Minsky vs. Neural Networks

Minsky vs. Neural Networks

One of the most controversial aspects of Minsky's legacy is his critique of neural networks.

In 1969, Minsky and Seymour Papert published Perceptrons, which highlighted limitations of early neural networks. While mathematically correct, the book discouraged funding for neural network research. As a result, it contributed to the first AI Winter, delaying deep learning's rise by decades.

Ironically, Minsky himself had built early neural networks, but he believed they were insufficient alone to explain intelligence. History would eventually vindicate both sides. Neural networks became powerful and symbolic reasoning remains unsolved. The modern AI boom is, in many ways, a reconciliation of Minsky's critique and neural learning.

Artificial Intelligence, Consciousness, and Emotion

Artificial Intelligence, Consciousness, and Emotion

Unlike many engineers, Minsky the philosopher embraced difficult questions:

- Can machines be conscious?

- Do emotions play a role in intelligence?

- Is free will an illusion?

In his book The Emotion Machine (2006), he argued that emotions are cognitive tools, that human intelligence depends on layered reasoning, and rationality alone is insufficient. This perspective deeply influenced affective computing, human-AI interaction, and modern discussions of AI alignment.

Minsky saw intelligence as messy, layered, and deeply human.

Minsky's Personality

Minsky's Personality

Provocative and often polarizing, Minsky was famous for his sharp wit, fearless claims, and a disdain for intellectual (and personal) conformity.

He often predicted boldly that human-level AI was just decades away, that consciousness could be engineered, and human minds were not special. While many predictions proved premature and others are controversial, his confidence helped legitimize AI as an ambitious scientific endeavor rather than a narrow technical specialty.

He was confident and unorthodox in his personal space as well. A former co-worker described the living room in his Boston home:

[Minsky's] living room wasn't simply a residence. It was a memory palace. A living archive of invention. Books leaned into modular synthesizers, brass instruments curled around CRT monitors, and a mannequin stood near the fireplace, locked in conversation with a kaleidoscopic sculpture suspended from the ceiling. Screens blinked beside dusty reel-to-reel machines. A piano waited quietly, still tuned for hands that would never return. You didn't look at this room - you entered it. And once inside, it felt less like stepping into someone's house than stepping inside a mind.

Influence on Modern AI

Influence on Modern AI

Though Minsky did not live to see ChatGPT, his influence is everywhere:

- Modular architectures resemble Society of Mind

- Debates about symbolic versus neural AI echo his arguments

- AI safety discussions reflect his concerns about uncontrolled intelligence

- Agent-based systems mirror his multi-process view

Modern AI labs still wrestle with the same questions Minsky raised in the 1960s.

Legacy: Vision Beyond His Time

Legacy: Vision Beyond His Time

Minsky received many accolades and honors, including the 1969 ACM Turing Award, the highest award in computer science.

Minsky received the Turing Award for his central role in creating, shaping, promoting, and advancing the field of Artificial Intelligence, and later honors like the BBVA Frontiers of Knowledge Award and the Dan David Prize.

Minsky mentored a generation of AI researchers at MIT and helped define AI's early culture and ambitions. Some contemporaries even said that he practically invented artificial intelligence.

Marvin Minsky died in Boston in 2016, just as deep learning began its explosive rise, yet his ideas remain foundational. In his long, productive life he gave AI intellectual legitimacy, philosophical depth, and fearless ambition. He was not always right, but he was never small-minded.

The Mind That Built Minds

The Mind That Built Minds

Marvin Minsky believed that understanding intelligence was humanity's greatest challenge and greatest opportunity.

He treated the mind not as a sacred mystery, but as a system worthy of study, debate, and construction. In doing so, he helped launch one of the most transformative forces in human history.

Artificial intelligence today stands on layers of code, data, and silicon. Beneath it all lies an idea Minsky championed: That the mind itself is a machine we can one day understand.

Links

Links

Biographies index page. Includes Alan Turing, John McCarthy, and other AI pioneers.

AI in America chapter on the Birth of AI.

External links open in a new tab.

- fi.edu/en/awards/laureates/marvin-minsky

- quantumzeitgeist.com/marvin-minsky

- technologyreview.com/what-marvin-minsky-still-means-for-ai

- datategy.net/ai-origins-marvin-minsky

- amturing.acm.org/award_winners/minsky

- news.mit.edu/marvin-minsky-honored-for-lifetime-achievements-in-artificial-intelligence

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marvin_Minsky

- britannica.com/biography/Marvin-Minsky

- mit.edu/~dxh/marvin/web.media.mit.edu/~minsky/minsky

- kalayjian.medium.com/the-philosopher-who-tried-to-give-machines-a-soul