AI in America

AI in America

Sample from the forthcoming book by AI World

The Dartmouth Conference

The Dartmouth Conference

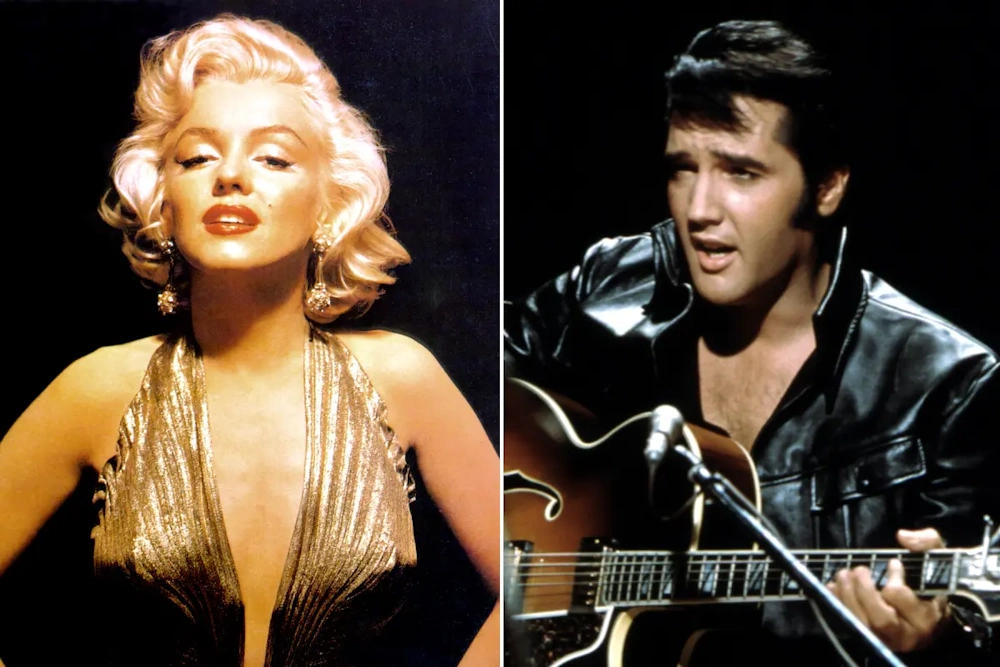

1956 was a banner year in America. Dwight David Eisenhower, General of the Army, a five-star, and hero of the Second World War, was re-elected President of the United States of America in a landslide. The Yankee's Mickey Mantle also had a great year, winning the Triple Crown with a .353 batting average, hitting 52 home runs, and driving in 130. Marilyn Monroe launched her acting career, starring in several movies and creating Marilyn Monroe Productions to have more control over her projects. Elvis Presley had a breakout year too, appearing on the Ed Sullivan TV show and producing number one hit songs with "Heartbreak Hotel", his first national #1 hit, "Hound Dog", "Don't Be Cruel", and "Love Me Tender". Teflon pans were invented in 1956, Dear Abbey answered her first letter, and the motto "In God we Trust" was authorized.

1956 was a very big year indeed in America, but there was one significant event that went larely unnoticed. In a small town in New Hampshire several academics met to discuss a topic few in America knew anything about. The scholars met in the mathematics hall of Dartmouth College to study something called "artificial intelligence":

"We propose that a 2-month, 10-man study of artificial intelligence be carried out...The study is to proceed on the basis of the conjecture that every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it."

The organizer of the event was John McCarthy, Assistant Professor of Mathematics at Dartmouth. Born in Boston to immigrant parents, McCarthy was educated at Caltech, the renowned California Institute of Technology, where his interest in computing was piqued when he attended a lecture from John von Neumann, the man acknowledged as the "father of modern computing" for his creation of the von Neumann architecture, the basis of modern digital computer design.

After graduating from Caltech in 1948, McCarthy went cross-country to Princeton, New Jersey, for his PhD, being closer to his New England roots and to the center of intellectual thought in America. Princeton University's influence in the early 1950s was immense, shaping the trajectory of mathematics, physics, and computer science, with thinkers like Albert Einstein, John von Neumann (whom he met at Caltech), Alonzo Church, Kurt Godel, and Robert Oppenheimer (scientific director of the Manhattan Project). Princeton was one of the leading centers for mathematics and theoretical research, home to some of the greatest minds in mathematics, a perfect setting for McCarthy's interests in math and computing. McCarthy was particularly drawn to Princeton because of its strength in mathematical logic, a field that would later become central to his work in AI.

McCarthy earned his Ph.D. in mathematics from Princeton University in 1951, where he studied under Solomon Lefschetz and worked on topics related to mathematical logic and computation. Upon graduation, McCarthy landed a job at IBM's Thomas J. Watson Research Center in Poughkeepsie, New York. This location was one of IBM's primary research and development hubs during that time. Home to Vassar College, Poughkeepsie is located in the Hudson Valley region of New York, approximately 75 miles north of New York City, not far from Princeton.

McCarthy joined IBM at a time when the company was at the forefront of computing innovation. IBM was developing some of the earliest commercial computers, such as the IBM 701. McCarthy collaborated closely with Nathaniel Rochester, a man who was instrumental in bringing McCarthy to IBM. Rochester shared McCarthy's interest in machine intelligence and supported his early explorations into AI. Together, they worked on developing programs that could simulate human reasoning and problem-solving, laying the groundwork for AI research. At IBM, McCarthy began experimenting with programs that could perform tasks requiring intelligence, such as playing chess and solving mathematical problems. One of his notable projects was developing a program to play chess, which was one of the earliest attempts to create a machine capable of strategic thinking. Although the program was rudimentary by today's standards, it was a significant step toward understanding how machines could simulate human thought processes.

McCarthy's work at IBM reinforced his interest in formal logic as a foundation for AI. He began exploring how logical reasoning could be implemented in machines, an idea that would later become central to his development of LISP and other AI systems. While at IBM, McCarthy began thinking about ways to make computing more efficient and accessible. This led to his early ideas about time-sharing, a system that would allow multiple users to interact with a computer simultaneously. Although time-sharing was not fully realized during his time at IBM, McCarthy continued to develop the concept later in his career, and it became a cornerstone of modern computing.

John McCarthy left IBM in 1953 to pursue academic opportunities that aligned more closely with his interests in AI and theoretical computer science. McCarthy was deeply interested in exploring theoretical questions about computation and intelligence, which were not the primary focus of IBM's industrial research at the time. Academia offered him the freedom to pursue these ideas without the constraints of corporate priorities. At IBM, McCarthy worked on practical computing problems, but his passion lay in the theoretical foundations of AI and formal logic. Moving to an academic setting allowed him to focus on these areas and collaborate with like-minded researchers.

McCarthy was offered a position at Dartmouth College as Assistant Professor of Mathematics, an opportunity to teach and conduct research in a more flexible and intellectually stimulating environment. Dartmouth was interested in fostering interdisciplinary research, which aligned with McCarthy's vision for AI. Soon after his appointment, McCarthy launched an effort to bring visionaries together that shared his passion. He chose to organize a conference as a way of achieving his goals for AI because it could provide a platform for collaboration, legitimize the field, generate needed momentum, and help to secure funding.

But a key question remained as to how to organize the conference, how to bring people together, and most importantly, how to get funding. McCarthy decided to reach out to his contact list, an impressive network of all-stars in industry and academia for a man so early in his career. First, there was Marvin Minsky, fellow graduate student at Princeton, who became a professor at Harvard after receiving his PhD at Princeton. Second, there was former colleague Nathaniel Rochester, the man who helped bring McCarthy to IBM. Finally, McCarthy reached out to Claude Shannon, a legendary figure in the scientific community. McCarthy met Shannon in 1952 when McCarthy interned at Bell Labs where Shannon was a researcher. Shannon's work on information theory had laid the groundwork for the digital revolution when he published his seminal 1948 paper "A Mathematical Theory of Communication". McCarthy and the others were stars; Shannon was the MVP, the key piece of the puzzle to get publicity and funding.

Google Doodle of Claude Shannon

Together--McCarthy, Minsky, Rochester, and Shannon--collaborated on the proposed conference of intellectuals. McCarthy wrote the draft of the proposal and circulated it to Minsky, Rochester, and Shannon. The final draft was submitted to the Rockefeller Foundation for funding. The Rockefeller Foundation was well known for funding innovative and interdisciplinary research projects. The foundation had a history of supporting scientific endeavors that pushed the boundaries of traditional disciplines. The proposal for the conference aligned with the foundation's mission to advance knowledge. McCarthy knew that securing funding from a prestigious organization like the Rockefeller Foundation would lend credibility to the conference and help attract top researchers. The involvement of prominent figures like Claude Shannon and Nathaniel Rochester enhanced the proposal's credibility.

"A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence" was submitted to the Rockefeller Foundation in August 1955, and funding in the amount of $7,500 (about $80k today), half of what they requested, was granted in late 1955. The goals of the project were to explore the potential of machines to simulate human intelligence and establish artificial intelligence as a legitimate field of study. Due to harsh New England winters, the organizers planned to hold the conference in the summer of 1956. This timeframe also allowed college professors to attend while on summer break, away from their teaching and researching duties.

Every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it.

The Summer of 1956

The Summer of 1956

In the summer of 1956, on the campus of Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, a small but remarkable gathering took place. The gathering was the eight-week workshop that would become known as the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence. This meeting is widely regarded as the founding event of the field of Artificial Intelligence, marking the birth of AI.

Founded in 1769, Dartmouth College combines deep historical significance with a rich tapestry of enduring student traditions, making it a unique Ivy League institution steeped in culture, academics, and community life. Dartmouth College was established in 1769 by Congregational minister Eleazar Wheelock in Hanover, New Hampshire, as a school dedicated to educating both Native Americans and English youth. Samson Occom, a Mohegan Indian and one of Wheelock's first students, played a critical role in raising funds for the College's founding.

The college's picturesque 269-acre campus along the Connecticut River is praised for its natural beauty. President Dwight D. Eisenhower once remarked, "This is what a college should look like." The bucolic college atmosphere was fitting for a meeting of minds, representing the greatest computer scientists in America.

What follows is a reconstruction of the day-by-day rhythm, structure, and interactions of the workshop held at Dartmouth, including how ideas were exchanged, and how the future of AI took shape. The reconstruction is based on archival notes, participant recollections, and historical accounts, in order to give a sense of what it felt like to be there, to be a part of history.

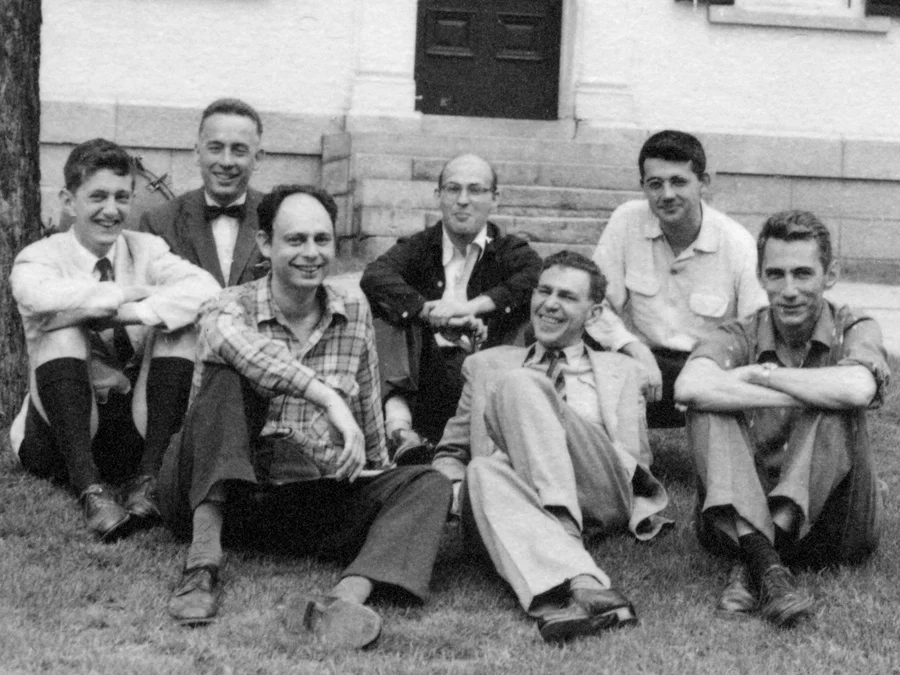

As the proposal outlined, the study lasted for eight weeks and involved nine core participants. These were the principals--McCarthy, Minsky, Rochester, and Shannon--plus five other participants:

-

Allen Newell and Herbert Simon, both from the Carnegie Institute of Technology (later called Carnegie Mellon). Newell and Simon created the Logic Theorist, an early AI program that proved mathematical theorems. The demonstration of the Logic Theorist was one of the top attractions of the conference.

-

Ray Solomonoff, mathematician, who developed algorithmic probability theory, a foundation for modern machine learning. Solomonoff, a lifelong friend of Minsky, took notes during the conference, providing his impression of the talks and ideas generated from various discussions. Ray's notes form the basis of his wife Grace's recollection of events and ideas.

-

Oliver Selfridge from MIT, called the "Father of Machine Perception" for his work on pattern recognition and early neural networks that helped shape the field of computer vision.

-

Trenchard More, mathematician, who made contributions to symbolic logic and reasoning. Trenchard also took notes during the conference.

Other researchers include Julian Bigelow, D.M. MacKay, and John Holland. McCarthy's participant list also included W. Ross Ashby, W.S. McCulloch, Abraham Robinson, Tom Etter, John Nash, David Sayre, Arthur Samuel, Kenneth R. Shoulders, and Alex Bernstein. Collectively, this group comprises the key computer science researchers of the time, academic and institutional, spanning a diverse set of technologies, interests, and beliefs.

June 1956

June 1956

The workshop opened, with participants arriving in New Hampshire, around June 18. Early arrivals included McCarthy, Solomonoff, and Minsky, while others filtered in day by day.

Participants settled in the next week, the first week of summer. Accommodation arrangements found many staying at the Hanover Inn or in faculty apartments. Informal gatherings occurred in the evenings. These get togethers included eating dinner at the Hanover Inn, taking walks on campus, and holding initial discussions about agenda and topics. One of the key topics discussed was: "Could a machine simulate every aspect of learning?" This question was framed in the original proposal.

The top floor of the Mathematics Department in Kemeney Hall at Dartmouth became the workshop's home, where the math-building rooms were set up for daily sessions.

The agenda for the workshop was laid out by the organizers (McCarthy and Minsky) to explore the following topics:

1. Automatic Computers: How to program computers to

simulate higher-level cognitive functions.

2. How to make a machine use

language: The foundational problem of Natural Language Processing (NLP).

3. Neuron Nets: The study of how to build machines based on idealized nerve

nets.

4. The Theory of the Size of a Calculation: Exploring complexity

theory and computational limits.

5. Self-Improvement: How to program

machines to improve their own programming (machine learning).

6.

Abstractions: How to program machines to form abstractions and concepts.

7. Randomness and Creativity: How to incorporate randomness and true

creative behavior into machines.

In short, the agenda was to propose and explore all facets of creating thinking machines.

On June 25, the first formal group session was held. McCarthy opened with remarks reviewing the proposal's grand claim: "Every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it." Roughly following the agenda, the subsequent discussions were wide-ranging, especially the structure of language, neural nets, algorithms, and the simulation of human problem-solving. One participant noted the room had "the dictionary on a stand" which they used to look up the term "heuristic", meaning an approach to problem solving that employs a pragmatic method that is not fully optimized, perfected, or rationalized, but is nevertheless 'good enough' as a first approximation. As the first AI conference in America, a heuristic approach was more than enough.

July 1956

July 1956

The core work of the conference was conducted during the month of July of 1956 with weekday presentations, wide ranging discussions, tours, and demonstrations.

Every weekday morning, starting at 9am, one of the attendees gave a short presentation or conducted a lead discussion. Typical speakers included Allen Newell, Herbert Simon, Oliver Selfridge, Julian Bigelow, and Claude Shannon.

Later in the morning, there were general discussions with multiple participants contributing thoughts. These continued over lunch where there were informal conversations at Hanover Inn or walking meetings around the Dartmouth campus.

Breakout sessions with pairs or small groups working on problems (symbolic logic, language translation, neural analogy) were conducted in the afternoon. Some visited IBM or other labs for adjunct visits.

In the evening there were informal talks, further discussions, and sometimes guest presentations. Solomonoff's notes indicated that Claude Shannon visited on July 10.

By Mid July (~July 10-20) , the group focused on "heuristics" and symbolic methods versus inductive methods. As noted, "We gathered around a dictionary on a stand to look up the word heuristic."

In one informal session, Newell and Simon demonstrated the Logic Theorist program (which could prove theorems). This demonstration excited many and set the tone for AI as a discipline of machine reasoning.

Participants debated whether simple rule-based systems or learning systems (probabilistic) would dominate. Ray Solomonoff kept detailed notes of these debates.

Even though attendance varied in late July, where several came for short stays only, the core group of McCarthy, Minsky, Solomonoff worked almost continuously. Many others visited for a week or two. They carved out research directions, including language processing, neural nets, abstraction, and self-improvement of machines.

The weekends were reserved for exploring Hanover and the New Hampshire countryside, but also for informal brainstorming sessions over dinner. The mix of leisure and idea-generation created a unique collaborative culture.

August 1956

August 1956

By the first week of August, the conference was winding down and the group shifted into wrap-up mode with final talks and future plans. What was planned for six weeks lasted eight.

By early August, several participants (e.g., Allen Newell, Herbert Simon) had already left. The remaining core discussed what had been achieved and what remained open. A key session held on August 15 featured Julian Bigelow giving a talk, according to Solomonoff's log.

The final group meeting was held on August 17. Concluding presentations by McCarthy and Minsky summarized progress, and drafted what would become a research agenda for AI.

Looking back, participants described the event as "very interesting, very stimulating, very exciting." They recognized that the ambition to make machines "use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans" was bold. But they also saw that real progress would require more than a summer.

Participants then left Dartmouth, carrying their ideas back to institutions like MIT, IBM, Stanford, etc.

Successes of the Dartmouth Conference:

-

Formal Establishment of the Field: The conference is recognized as the birth of the discipline, successfully coining the term "Artificial Intelligence" and defining a comprehensive research agenda that included language, neural nets, self-improvement, and abstraction.

-

Uniting the Founders: It brought together the key pioneers (Minsky, McCarthy, Simon, Newell, etc.) who would establish the major academic research centers (MIT, Stanford, CMU) that dominated AI development for the next several decades.

-

Validation of Symbolic AI: The presentation of Newell and Simon's Logic Theorist program demonstrated that a machine could successfully prove mathematical theorems using symbolic reasoning, lending credibility to the entire enterprise. The Logic Theorist program is often considered the first true artificial intelligence program, designed to mimic human problem-solving and prove symbolic logic theorems.

Failures of the Dartmouth Conference (In Retrospect)

-

Unrealistic Optimism: The participants were grossly over-optimistic about the speed of progress, famously suggesting that the problem of AI could be largely solved within a single summer or a decade. This led to exaggerated funding promises and subsequent periods of disillusionment and "AI Winters."

-

The Symbolic Bias: The conference strongly favored the symbolic approach to AI (using logic and rules) over the connectionist approach (neural networks). This bias led to decades where neural network research was largely abandoned, severely delaying the development of the deep learning techniques that now define modern AI.

-

Underestimation of Compute: The attendees did not fully appreciate the sheer computing power and massive datasets required to make generalized intelligence a reality.

Significance of the Dartmouth Conference

The conference attendees represented a virtual who's who of early computing and cognitive science. There was Herbert Simon, Allen Newell, Ray Solomonoff, Oliver Selfridge, and others who would each go on to pioneer subfields of AI in the years to come. What made the Dartmouth Conference unique was not its size, but its purpose of bringing together mathematicians, computer engineers, psychologists, and philosophers with a common goal. That goal was to understand intelligence by building it.

While the historical record of the day-to-day discussions is limited, surviving letters, notes, and recollections paint a vivid picture of the conference procedings. McCarthy and Minsky led open discussions on reasoning and symbolic logic. Simon and Newell demonstrated early versions of their Logic Theorist program, which could prove mathematical theorems, an astonishing feat in 1956. Shannon presented on information theory and its implications for communication and perception. Rochester discussed IBM's early computing capabilities and the potential for digital machines to learn.

Though no single breakthrough emerged during those weeks, the atmosphere was electric. Attendees debated whether the human brain was best modeled by symbols or neurons, whether learning could emerge from feedback loops, and whether computers might one day rival the mind itself.

Out of Dartmouth grew many of the first major AI research centers: MIT's AI Laboratory, Stanford's AI Group, Carnegie Mellon University's AI Department, and IBM's early research in computational reasoning. The participants returned to their institutions and built teams, secured funding, and began decades-long experiments that defined the direction of modern computing. Herbert Simon later remarked, "What happened at Dartmouth in 1956 was not so much the birth of a field as the naming of one." Indeed, the term "Artificial Intelligence", coined by McCarthy for the proposal, gave coherence and identity to an idea that had been percolating through multiple disciplines.

The timing of the conference was no accident. America's Cold War ambitions, which we discuss in the next chapter, were fueling massive investments in science and technology. The military saw potential in machines that could "think." Thinking machines could be used for navigation, communication, and even strategy. AI thus became a beneficiary of new federal research programs, notably through DARPA (the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency), founded and funded just two years later in 1958. The spirit of Dartmouth fit neatly into the narrative of American innovation and technological supremacy.

The 1956 meeting didn't produce an immediate revolution, but it did lay the foundation for one. Every era of AI that followed, from the symbolic AI of the 1960s, to the expert systems of the 1980s, to the deep learning renaissance of the 2010s, can trace its roots back to those discussions in Hanover. The "Dartmouth spirit" was one of interdisciplinary collaboration, intellectual boldness, and optimism; qualities that continue to define AI research today. John McCarthy would go on to create LISP, one of the earliest programming languages for AI; Minsky co-founded the MIT AI Lab; Simon and Newell helped establish the field of cognitive psychology; and Shannon's theories became the backbone of digital communication.

In retrospect, the Dartmouth Conference was more than an academic event. It was a declaration of intent. It placed the United States at the center of a technological frontier that would eventually transform the world economy, redefine work, challenge ethics, and reshape human identity. AI may be global today, but its intellectual birth certificate bears an American address: Dartmouth College, Summer 1956.

The Dartmouth Conference did not end with a triumphant breakthrough, but with a shared conviction that thinking machines were possible, and their creation would require decades of steady, interdisciplinary effort. What began in a small New Hampshire classroom soon radiated outward into universities, corporate research centers, and the newly expanding defense laboratories of the United States. As the attendees dispersed, they carried with them ideas that would seed the first AI departments, influence early programming languages, and inspire a generation of researchers who viewed intelligence as something that could be engineered.

The timing of Dartmouth's vision was no accident. The mid-1950s marked not only the birth of AI, but also the height of geopolitical tension. The same computational power required to model reasoning and perception was also needed to simulate nuclear trajectories, decrypt Soviet communications, and guide missiles with unprecedented precision. As America moved deeper into the Cold War, artificial intelligence research--born in academic curiosity--was quickly swept into a national struggle for technological supremacy.

The next chapter traces how AI left the seminar rooms of Dartmouth and entered the highly charged world of Cold War computing, where the race for smarter machines became inseparable from the race to defend a nation.

Links

Links

AI in America home page

Biographies of AI pioneers

External links open in a new tab:

- raysolomonoff.com/dartmouth/dartray.pdf

- everything.explained.today/Dartmouth_Summer_Research_Project_on_Artificial_Intelligence/

- admissions.dartmouth.edu/follow/3d-magazine/dartmouth-and-dawn-ai

- spectrum.ieee.org/dartmouth-ai-workshop

- aiws.net/the-history-of-ai/this-week-in-the-history-of-ai-at-aiws-net-the-dartmouth-conference-ended-on-17th-august-1956

- historyofdatascience.com/dartmouth-summer-research-project-the-birth-of-artificial-intelligence