After Dartmouth

After Dartmouth

Sputnik and ICBMs

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union's R-7 Semyorka, the world's first Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM), launched a satellite into outer space. It was called Sputnik and, seemingly overnight, it changed everything. It was difficult for Americans to comprehend how a 180 pound metal sphere could orbit the Earth in less than the time it takes to watch a movie, and not fall from the sky. What Americans could comprehend was the newfound ability of the USSR to hit the USA with a nuclear bomb riding atop an R-7 ICBM. Whether it was an actual threat or not, the prospect of Soviet rockets reaching US airspace was a wake-up call for America. And it got to work immediately.

Aside from some vague fears and scattered media hype about "electronic brains" taking over jobs or even humanity, there was little thought of the concept of artificial intelligence in 1957. American culture was marked by post-war prosperity, the rise of consumerism, Cold War tensions, and early signs of social change that would characterize the next decade.

The post-war economic boom was in full swing, with a strong middle class, suburban expansion, and increased consumer spending. The Interstate Highway System (approved in 1956) expanded, making road trips and suburban commutes easier. Cars like the Chevy Bel Air and Ford Fairlane were symbols of American freedom. Over 40 million U.S. homes now had TVs and America watched popular shows like "I Love Lucy", although the final episode aired in 1957, and "Leave It to Beaver", which had its debut in 1957. "The Ed Sullivan Show" was immensely popular, especially when it featured rock 'n' roll performers like Elvis Presley.

Feeling threatened by the new Soviet technology, America responded by establishing NASA, founded DARPA, launched Explorer, the first US satellite, and enacted the National Defense Education Act (NDEA), pouring millions of dollars into science and technology education and institutions. Artificial Intelligence was the indirect recipient of some of the funds made possible by programs like NASA, DARPA, and NDEA. While these programs didn't write checks for AI, they in effect trained the people, built the labs, and developed the computers that made AI research possible.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is one of the best known, and highest funded, US government agencies. Its success culminated in putting men on the moon as part of the space race in the 1960s and beyond...

The NDEA is less well known to the general public, but very well known to educational institutions that received funding for research projects, including AI research. The NDEA was the unseen catalyst of AI; funding the foundations of AI like university computer science programs, supporting key AI ancillary fields such as mathematics for algorithms and logic-based AI, and feeding talent into defense-AI projects like LISP.

John McCarthy, fresh off the Dartmouth Conference of 1956, was the recipient of some of these funds. He invented LISP (an acronym for LISt Processor) in 1958, the first programming language designed specifically for AI research. Its elegant design, flexibility, and symbolic processing capabilities made it the dominant language in AI for decades. The insight for LISP came from the Dartmouth Conference, from Newell and Simon's presentation of the Logic Theorist.

Cold War Computing: The U.S. Military's Role in AI Development

During the Cold War (1947-1991), the U.S. military played a crucial role in funding and advancing artificial intelligence (AI) and computing technologies. This section explores how the race for technological superiority against the Soviet Union led to major breakthroughs in computer science, machine learning, and automation, many of which laid the foundation for modern AI.

During the Cold War, the U.S. government and military saw AI and computing as critical for:

-

Cybernetics and Command Systems: Enhancing military decision-making and automation.

-

Cryptography and Codebreaking: Decrypting enemy communications (e.g., SIGINT, NSA projects).

-

Autonomous Weapons and Defense: Early research into unmanned systems and automated targeting.

-

Spy Satellites and Intelligence: Using AI for surveillance and data analysis.

-

Simulation and War Games: Training simulations to model nuclear conflicts.

These expert systems influenced modern AI-driven decision-making and automation. The Department of Defense (DoD) and organizations like ARPA (later DARPA) provided massive funding to universities and private companies, accelerating the development of AI.

The most pressing threat during the Cold War was a surprise nuclear attack, particularly after the Soviet Union tested its first atomic bomb in 1949 and launched Sputnik in 1957. A bomber or missile attack would grant decision-makers only minutes--or even seconds--to detect, analyze, and respond. Human reaction speed was simply too slow for this new speed of warfare.

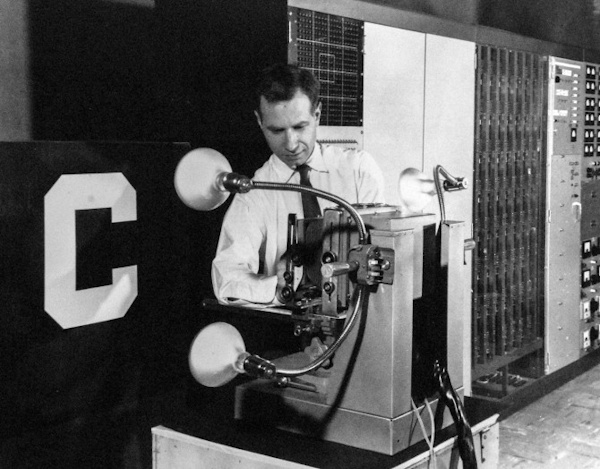

The military required systems that could automate the decision loop, leading to the development of the first large-scale, real-time computing project. It was called SAGE and it stood for Semi-Automatic Ground Environment. Initiated in the early 1950s, SAGE was a massive, centralized air defense system designed to automatically track Soviet bombers approaching North America, calculate intercept trajectories, and guide U.S. interceptor aircraft or missiles. While termed "semi-automatic" because humans retained the final command role, SAGE was a proto-AI system. It was the first system to integrate radar data from hundreds of sources, process it in real-time, and make automatic tactical recommendations. One of the first real-time computerized air defense systems, this project, developed by MIT and IBM and funded by the U.S. Air Force, pioneered dozens of technologies critical to later AI, including real-time operating systems, digital networking, time-sharing computers, and interactive display terminals.

The primary goal of DoD was to secure an advantage over the USSR by focusing on superior technology rather than manpower or sheer quantity of arms. AI was seen as the ultimate tool for achieving this technological feat.

The Creation of ARPA (DARPA)

Sputnik was a wake-up call for the USA. In response, President Eisenhower established the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) in February 1958. ARPA's primary mission was simple yet expansive; to regain American technological superiority. ARPA was the agency responsible for funding "high-risk, high-reward" research and development that often lies far beyond the immediate needs of the military services.

ARPA was formally renamed the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to emphasize its military and national security focus. DARPA's success is attributed to its unique, non-bureaucratic operational structure. The structure was small and agile and funded to tackle the high-risk, high-reward projects that push tech boundaries. These were projects too wild or speculative for conventional military and commercial research and development groups. DARPA didn't invent AI, but it turbocharged the field post-Dartmouth era with cash, vision, and military goals that over time turned into commercial windfalls.

DARPA artificial intelligence (AI) programs have

emphasized the need for machines to perceive and interact with the world

around them; to frame problems and to arrive at solutions and decisions

based on reasoning; to implement those decisions, perhaps through

consultation with a human or another machine; to learn; to explain the

rationale for decisions; to adhere to rules of ethical behavior defined for

humans; to adapt to dynamic environments; and, to do all of this in

real-time. In short, DARPA has always been interested in AI frameworks that

integrate AI and computer science technologies, and the application of those

frameworks to DARPA-hard problems.

-DARPA Mission Statement.

Right after its founding, DARPA latched onto AI as a strategic asset. By the early 1960s, it was bankrolling key university labs and became the the primary funding source for academic AI research centers at MIT, Stanford Research Institute (SRI), and Carnegie Mellon University. These were institutions of higher learning where Dartmouth attendees and AI leaders like John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, and Allen Newell worked. MIT's AI Lab (founded in 1959) got DARPA grants to explore symbolic AI and perception with grants of tens of millions of dollars spread over decades. Post-Sputnik, DARPA pushed AI for Russian-to-English translation to decode Soviet intelligence. Early efforts in the 60s were crude and rule-based, not fluent, but they laid the groundwork for technologies like natural language processing. DARPA funding allowed researchers to explore general problem-solving, planning, and knowledge representation, leading to early AI successes like:

-

MIT's "Machine-Aided Cognition" (later called simply the AI Lab), backing time-sharing systems, and conducting AI research. This birthed MULTICS, a precursor to the UNIX operating system, and supported McCarthy's work on LISP. Project MAC led to early developments in machine learning and natural language processing.

-

At Stanford Research Institute (SRI), DARPA funded Shakey the Robot, the first mobile robot that could reason about its surroundings, plan complex actions, and learn from experience. It used cameras, sensors, and planning algorithms to navigate rooms, which was a huge advance for robotics and computer vision. The cost was $750K ($5M today).

Shakey was the first general-purpose mobile robot capable of perceiving and reasoning about its environment to perform tasks such as planning, route-finding, and rearranging objects. Shakey combined research in robotics, computer vision, and natural language processing, pioneering techniques like the A* search algorithm and the Hough transform. It was called the "first electronic person" by Life magazine in 1970 and is considered a landmark in AI and robotics history. Technologies such as cell phones, global positioning systems (GPS), Roomba and Optimus, and self-driving vehicles have become a reality and simplified life thanks to the inspiration of Shakey.

The NSA and AI for Cryptography

At the end of World War II, the United States made a strategic decision that would define the intelligence landscape for decades: never again would America be blind to foreign communications. After Allied success cracking ENIGMA and Purple in World War II (led by Alan Turing), U.S. officials understood that signals intelligence (SIGINT) was the new high ground of national security. The immediate postwar years saw ad-hoc organizations attempting to collect and decode foreign communications, but they lacked centralized authority. This changed on November 4, 1952, when President Harry S. Truman quietly signed a top-secret memorandum creating the National Security Agency (NSA). Truman created an agency so secret that for years its very existence was barely acknowledged. Initially, the NSA's mission was simply to intercept foreign communications and protect U.S. communications. As the Cold War was already accelerating, its role quickly expanded.

Long before machine learning became a household term, the NSA pioneered early computational techniques like high-speed cryptanalysis, pattern recognition, automated language processing, and early forms of computer-based codebreaking. The agency operated some of the fastest computers in the world, often decades ahead of commercial technology. Their machines analyzed enormous volumes of radio chatter, telegraph signals, and encrypted messages. The NSA invested heavily in pattern recognition and machine learning to break Soviet codes, and used AI-powered heuristic search algorithms to analyze encrypted messages. These efforts influenced later developments in natural language processing (NLP) and AI security applications. Some historians consider NSA codebreaking systems the earliest ancestors of modern AI-driven surveillance.

The Perceptron and Neural Networks (1958)

In the summer of 1958, on a naval research base in upstate New York, a young psychologist named Frank Rosenblatt introduced a machine that would become one of the most consequential creations in the early history of artificial intelligence: the Perceptron. It was simple. It was flawed. It was decades ahead of its time. The Perceptron did not just launch neural networks, it sparked some of the earliest hopes and deepest fears about whether machines could learn, think, and eventually surpass their creators. To understand the rise of modern AI, one must first understand the improbable journey of the Perceptron.

Following Dartmouth and Sputnik, America in 1958 was a nation obsessed with learning machines. The late 1950s were a moment of intense scientific optimism in the United States. The Dartmouth Conference of 1956 had just coined the term artificial intelligence. The Sputnik crisis had triggered a national push for advanced research. Cybernetics, neuroscience, and computer science were converging into new ways of thinking about intelligence. Into this atmosphere stepped Frank Rosenblatt. Working at the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory and funded largely by the U.S. Navy, Rosenblatt wasn't trying to build a computer: he was trying to build a brain.

The original Perceptron was a hybrid of hardware and theory. The Mark I Perceptron was not merely software, it was a physical machine with sensors representing a retina, motors adjusting electrical weights, and hardware implementing learning rules. It looked more like a Cold War radar console than a computer, but it could do something astonishing for 1958: classify patterns it had never seen before. The theory is a Perceptron was a simple mathematical model inspired by neurons with inputs (simulated "dendrites"), adjustable weights, a summation unit, and a threshold-based output ("fire" or "don't fire"). If the Perceptron made a mistake, it could adjust its weights. This was the first widely known algorithm that allowed a machine to learn from experience.

The Perceptron software was the first algorithm capable of supervised learning, binary classification, incremental weight updates, recognizing handwritten letters or shapes, and generalizing from examples. Its learning rule, the Perceptron update rule, is still taught today as the basis for modern neural networks.

American newspapers and magazines erupted with excitement, calling it "The Machine That Thinks". Headlines claimed the Perceptron would soon walk, talk, reproduce itself, make scientific discoveries, and surpass human intelligence. Charismatic and confident, Rosenblatt fueled the hype. To many, the Perceptron felt like the first step toward mechanical thought. In retrospect, the claims were exaggerated, but its cultural impact was enormous. The Perceptron became America's first AI celebrity, long before ChatGPT existed.

Rosenblatt believed Perceptrons could be stacked into multiple layers to create powerful models. He was right, but he had no way to prove it. Computers were too slow, memory too small, and training too costly. The vision required decades of technological progress with GPUs, big data, and backpropagation before it could come to life.

In 1969, MIT researchers Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert published Perceptrons, a devastating critique of Rosenblatt's model. They showed that single-layer Perceptrons could not learn XOR, curved boundaries, and many real-world functions. Their conclusion was mathematically correct, and culturally destructive. Funding collapsed. Neural network research was abandoned. And Rosenblatt tragically died in a boating accident the next year. The Perceptron, once hailed as the future, became a cautionary tale. This backlash triggered the first AI winter, chilling research for nearly 15 years.

Although dismissed, the Perceptron planted the seeds of modern AI:

-

The Learning Paradigm: The idea that machines learn from data began here.

-

Model + Training Algorithm: The Perceptron was the first model that separated the architecture from the learning rule.

-

Neural Inspiration: It kept alive the idea that intelligence can emerge from networks of simple units.

-

The Foundation for Deep Learning: When backpropagation was rediscovered in the 1980s, it allowed Rosenblatt's dream of multilayer networks to finally work.

-

Cultural Impact: The Perceptron made AI a household term long before ChatGPT.

In essence, the Perceptron was the Wright Flyer of neural networks. It was primitive and limited, but historically transformational.

In the 2010s, with GPUs, massive datasets, and improved algorithms, multi-layer neural networks returned with speech recognition, image recognition (AlexNet, 2012), transformers (2017), and Generative AI (2020s). Every modern neural architecture, be it CNNs, RNNs, transformers, or LLMs, traces its lineage back to the Perceptron. Rosenblatt's model lives inside every AI system used today, from ChatGPT to Robotics. The Perceptron was not the future; it was the beginning.

The Perceptron matters because it Introduced learning machines to the world. Before 1958, computers followed instructions. After 1958, computers could adapt. It inspired AI's first philosophical questions. Could machines learn? Could they perceive? Could they rival humans? It set the stage for neural networks and deep learning. Without Rosenblatt, there is no AlexNet, no GPT, no Claude. It demonstrated the cyclical nature of AI progress. Hype to disillusionment to resurgence is a pattern repeated throughout AI history. And it showed the limits of early computing. Rosenblatt's idea was right in that technology simply wasn't ready.

The Perceptron was a primitive machine with enormous ambition. It could not do everything its creators hoped. But it did one thing that changed the world: It taught machines to learn. From a tiny lab in 1958 came the conceptual ancestor of every neural network, every generative model, every AI assistant, and the foundation of the modern AI revolution. The Perceptron was not merely a research experiment. It was the moment artificial intelligence gained a pulse.

AI and War Games: The RAND Corporation and Strategic AI

Long before Silicon Valley became the center of artificial intelligence, a different California institution--the RAND Corporation--quietly laid the intellectual foundations for the digital age. Formed in 1946 as a collaboration between the U.S. Army Air Forces and Douglas Aircraft, RAND was tasked with doing something unprecedented: using rigorous scientific analysis and mathematics to guide national security policy. Out of this mission emerged the earliest attempts to teach machines how to think, predict, strategize, and simulate conflict. Between 1947 and the end of the Cold War, RAND became the birthplace of many ideas that would later define modern AI, from game theory and machine reasoning to automated decision systems and computer-based war gaming. RAND did not build "AI systems" in the modern sense. RAND built the intellectual operating system that would make AI possible.

While universities like Dartmouth and MIT shaped AI as an academic field, RAND helped shape AI as a tool of national survival. Through game theory, war games, decision-making research, and early computational simulations, RAND gave America and the world the intellectual vocabulary of algorithmic strategy. RAND taught policymakers to think like machines. Decades later, machines began learning to think like policymakers. It is impossible to understand the origins of AI in America without recognizing RAND's profound and lasting influence. RAND is the bridge between the Cold War and the age of artificial intelligence, between nuclear strategy and algorithms, between human reasoning and machine logic.

The Rise of Expert Systems 1970s and 1980s

Long before deep learning, transformers, or generative models, there was a different vision of artificial intelligence, one rooted not in data, but in knowledge. In the 1970s and 1980s, AI researchers believed that if you could capture the logic, rules, and reasoning patterns of human experts, you could bottle intelligence itself. This vision gave rise to expert systems, America's first commercially successful wave of AI. They were the foundation of the nation's early AI industry, the driving force behind the first corporate AI boom, and a stepping stone to modern reasoning engines. For two decades, expert systems shaped medicine, finance, manufacturing, national defense, and the early culture of Silicon Valley. They represented the moment when AI escaped the lab and entered the boardroom.

DARPA funded the development of expert systems, AI programs designed to mimic human decision-making. Notable systems included:

-

MYCIN: AI for medical diagnosis (later adapted for battlefield medicine).

-

DENDRAL: AI for chemical analysis, useful in weapons detection.

-

XCON: AI used by the military to manage complex logistics and planning.

AI and The Cold War: Key Takeaways

Military-funded AI research during the Cold War led to:

-

The rise of neural networks and deep learning (Perceptron modern AI).

-

AI-powered cybersecurity and encryption (NSA research).

-

AI-based logistics and automation (DARPA projects).

-

Satellite intelligence and automated surveillance (leading to today's AI-powered geospatial analytics).

-

Natural language processing (NLP) (early AI models for translation and decryption).

The Cold War was not only a geopolitical struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union, it was also one of the greatest scientific accelerators in American history. Still in its infancy during this era, AI benefited enormously from military, defense, and intelligence agency investments. The race for technological superiority transformed AI from a theoretical academic pursuit into a strategic priority with global consequences. The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), now the Department of War, played a major role in shaping early AI. DARPA, NSA, and the RAND Corporation were key institutions driving AI development. Many AI breakthroughs of today trace their origins to Cold War-era military research, breakthroughs born in America we'll explore next.

Links

Links

AI in America home page

Biographies of AI pioneers

External links open in a new tab:

- aicadium.ai/the-evolution-of-ai/

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AI_winter

- linkedin.com/posts/jkeesh_in-1974-a-3m-ai-project-failed-so-badly-activity-7328437704428281861-2-nR

- pigro.ai/post/history-of-artificial-intelligence-1960s-1970s

- wsj.com/tech/ai/the-ai-cold-war-that-will-redefine-everything-4e1810b2