Google Doodles

Google Doodles

Famous depictions of the Google logo

Google Doodles are creative alterations of the Google logo that celebrate events like holidays and anniversaries, and the lives of famous scientists, artists, and pioneers. What started as a playful out-of-office message has evolved into a global phenomenon, featuring interactive games, animations, and even AI-powered experiences.

Over 5,000 Doodles have been created since 1998 when Google was founded as a company. Some Doodles are location-specific, like India's Independence Day. Many celebrate holidays, such as St. Patrick's Day. Do you have an idea for a doodle? At one time, users could submit Doodle ideas directly via Google's Doodle submission page, but alas the link has been removed. Instead, Google annually sponsors Doodle for Google contests.

Here are some of our favorite Google Doodles:

Alan Turing

Alan Turing was a completely original thinker who shaped the modern world, but many people have never heard of him. Before computers existed, he invented a type of theoretical machine now called a Turing Machine, which formalized what it means to compute a number.

The doodle for his 100th birthday shows a live action Turing Machine with twelve interactive programming puzzles (hint: go back and play it again after you solve the first six!). Turing's importance extends far beyond Turing Machines. His work deciphering secret codes drastically shortened World War II and pioneered early computer technology. He was also an early innovator in the field of artificial intelligence, and came up with a way to test if computers could think - now known as the Turing Test. Besides this abstract work, he was down to earth; he designed and built real machines, even making his own relays and wiring up circuits. This combination of pure math and computing machines was the foundation of computer science. As a human being, Turing was also extraordinary and original. He was eccentric, witty, charming and loyal. He was a marathon runner with world class time. He was also openly gay in a time and place where this was not accepted. While in many ways the world was not ready for Alan Turing, and lost him too soon, his legacy lives on in modern computing. Turing is a hero to us, so we wanted to make a special doodle for his centennial. We started by doing deep research into his work. Much of it is abstract and hard to show, so we went through a lot of designs before finding one that seemed workable. Turing Machines are theoretical objects in formal logic, not physical things, so we had to walk a fine line between technical accuracy and accessibility.

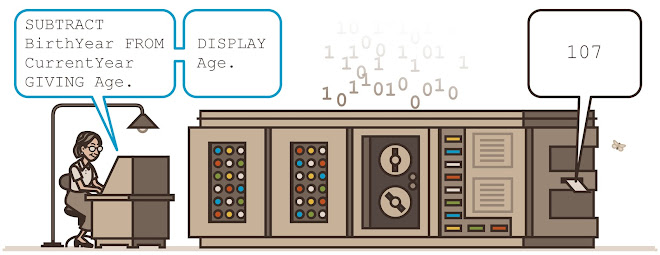

Grace Hopper

Grace Hopper was the woman who helped design one of the first modern programming languages. Hopper was a U.S. Navy Rear Admiral, and in 1959 she helped create COBOL, a program that the military and banks still use today.

Hopper, who would have been 107 today, also popularized the term "debugging" as a way of fixing computer glitches. She gets credit for coining the name of a ubiquitous computer phenomenon: the bug. In August 1945, while she and some associates were working at Harvard on an experimental machine called the Mark I, a circuit malfunctioned. A researcher using tweezers located and removed the problem: a 2-in. long moth. Hopper taped the offending insect into her logbook. Says she: "From then on, when anything went wrong with a computer, we said it had bugs in it." The moth is still under tape along with records of the experiment at the U.S. Naval Surface Weapons Center in Dahlgren, Va. Not only does "Amazing Grace" have this Google Doodle, but she's also got a Navy Destroyer (the USS Hopper) and a super computer (the Cray XE6 "Hopper") named after her. In 1987, she gave a commencement speech to Trinity College, saying: "There's always been change, there always will be change. It's to our young people that I look for the new ideas. No computer is ever going to ask a new, reasonable question. It takes trained people to do that. And if we're going to move toward those things we'd like to have, we must have the young people to ask the new, reasonable questions. A ship in port is safe; but that is not what ships are built for. And I want every one of you to be good ships and sail out and do the new things and move us toward the future." As one of the first visible women working on computers, Hopper is often a symbol for women who want to enter the world of mathematics and computers. The Anita Borg institute has a Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computer Conference, inspired by Hopper's legacy.

Ada Lovelace

Augusta Ada King, countess of Lovelace, along with her counterpart Charles Babbage, were pioneers in computing long before the first computer was built. Despite being an uncommon pedagogy for women, Ada was educated in mathematics because her mother hoped would mitigate in Ada her father's, Lord Byron's, penchant for poetry and mania (it didn't).

While Babbage drew up designs for the first general-purpose computer, which he called the Analytic Engine, he only imagined it would be a powerful calculator. Lovelace, however, anticipated the much more impressive possibilities for such a machine. She realized the engine could represent not just numbers, but generic entities like words and music. This intellectual leap is the foundation of how we experience computers today, from the words on this screen to the colors and shapes in this doodle. In 1843, Ada published extensive notes on the Analytic Engine which included the first published sequence of operations for a computer, which she would have input to the Analytic Engine using punch cards. It is this program for calculating Bernoulli numbers which leads some to consider Ada Lovelace the world's first computer programmer, as well as a visionary of the computing age.

Claude Shannon

Often called the "father of the Information Age," Claude Shannon (1916-2001) was an American mathematician, engineer, and the founder of information theory, the field that underpins all modern digital communication, computing, data compression, and cryptography. His 1948 paper, A Mathematical Theory of Communication, is widely considered one of the most important scientific papers of the 20th century, establishing the concept of the "bit" and defining how information can be quantified and transmitted reliably.

Shannon was born on April 30, 1916, in Petoskey, Michigan, and grew up in the nearby town of Gaylord. He showed early talent in mathematics and tinkering, building telegraph systems and mechanical gadgets as a teenager. Shannon earned two bachelor's degrees from the University of Michigan in mathematics and electrical engineering in 1936.

He then attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he completed both his master's and Ph.D. His master's thesis, A Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits, demonstrated that Boolean algebra could be used to design electrical circuits, an insight that became the foundation of digital computing.

Information Theory

Shannon's landmark 1948 paper introduced the bit as

the basic unit of information, the concept of entropy in communication, and

mathematical limits for data compression and error-free transmission. This

work created the theoretical basis for the internet, digital media, data

storage, and telecommunications.

Digital Circuit Design

Shannon's master's thesis showed that logic and

algebra could describe electrical circuits. This became the blueprint for

digital computers, influencing every generation of hardware design.

Cryptography and WWII Work

During World War II, Shannon worked at Bell

Labs on classified cryptography projects, including secure communication

systems used by Allied leaders. His work laid foundations for modern

cryptography and secure communications.

Artificial Intelligence and Robotics

Shannon built early AI

experiments, including a maze-solving mechanical mouse, a juggling robot,

and a machine that could play chess. These playful inventions reflected his

belief that creativity and curiosity drive scientific discovery.

The Birth of AI

Claude Shannon was one of the four organizers of the

1956 Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, the event

widely regarded as the founding moment of AI. He co‑designed the proposal

with John McCarthy,

Marvin Minsky, and Nathaniel Rochester, and helped shape

the workshop's agenda, which launched AI as a formal academic field. Shannon

made a difference to the conference as a bridge between disciplines as well

as an organizer. He connected mathematics, electrical engineering,

cryptography, communication theory, and early computing. This

interdisciplinary reach was essential for a field that didn't yet exist.

Shannon was also important to the conference as a counterbalance to pure

symbolic AI. While McCarthy and Minsky leaned toward symbolic logic, Shannon

brought probabilistic thinking, information‑theoretic reasoning, and a more

empirical, experimental mindset. This diversity of perspectives helped shape

AI's early identity.

Shannon received many of the highest scientific honors, including the National Medal of Science (1966), the IEEE Medal of Honor (1966), and the Harvey Prize (1972).

He spent most of his career at Bell Labs and MIT, becoming a central figure in 20th-century engineering and mathematics. Claude Shannon died on February 24, 2001, in Medford, Massachusetts, at age 84. His ideas continue to shape every digital device and communication system in the modern world.

✅Did you know: The Claude chatbot is named after Claude Shannon.

Links

Links

Biographies of AI pioneers.

External links open in a new tab:

- doodles.google/about

- doodles.google/search/?topic_tags=computer%20science&topic_tags=ai

- blog.google/products-and-platforms/products/search/google-doodles-show-how-ai-mode-can-help-you-learn

- lenovo.com/us/en/glossary/google-doodle

- joey-slikk-alt.fandom.com/wiki/List_of_Google_Doodles